Kyle Minor has published fiction and nonfiction in such literary magazines as Quarterly West, Carolina Quarterly, Mid-American Review, Sou'wester, and River Teeth. His work has also been honored by Writer's Digest and the Atlantic Monthly—where he earned awards in all three genres of the student writing competition—honorable mention in fiction and poetry in 2005, and second place in nonfiction in 2004. He is editor of Frostproof Review and has taught at Ohio State, Antioch, and Capital universities, and the Gotham Writers Workshop. He earned an M.A. in Creative Writing (Fiction Writing) from Antioch, and will this spring complete an M.F.A. in Fiction and Nonfiction from Ohio State.

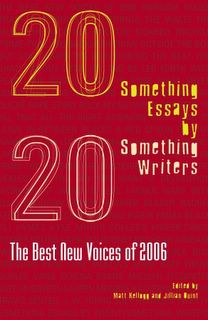

Most recently, Kyle's essay, "You Shall Go Out with Joy and Be Led Forth with Peace," a harrowing tale of the brutality of being bullied that also intelligently examines religious indoctrination, class, and race, was selected for inclusion in the Random House anthology Twentysomething Essays by Twentysomething Writers: The Best New Voices of 2006, edited by Matt Kellogg and Jillian Quint, and available in stores today, August 29th.

Kyle has kindly taken the time to sit down with me for a little virtual interview about writing in several genres, his writing plans for the future, and what it means to be anthologized.

* * *

CS: These kinds of "Best New Voices" anthologies are fairly common. Most of them I'm familiar with, however, showcase fiction, not essays. What do you make of this development?

KM: It seems that people these days are becoming more and more interested in literary nonfiction, especially the memoir. I hear it from my students all the time when I assign novels or short stories: "Why should we have to read this? It didn't really happen. It's not real!"

But that's not how I feel about it at all. Quite frankly, most of the memoir I read doesn't nearly begin to account for the sorry mess we can make of our lives the way good fiction can. Whenever I pick up, say, one of Philip Roth's Zuckerman novels, or Graham Greene's The Quiet American, or just about any of Andre Dubus's story collections, I feel like I'm communing with flesh and blood human beings. That's the same kind of transcendent experience I hope to offer my readers, whether they're reading my memoirs (which are, anyway, like fiction in the sense that they are a subjective rendering of things half-remembered, interpretations of memories of memories, because that's how our minds make sense of where and who we've been) or whether they're reading my fiction. I wish I could say that every story or essay I've published does this, but it's not true. I'm still learning, and it's hard as hell. I feel like I'm only starting to figure it out now, and I say that with fear and trembling.

CS: Since you do work rather extensively in both fiction and non-fiction, how do you go about deciding the best route toward attaining that transcendent experience? In other words, how do you decide whether material should be artfully rendered as fiction or non-fiction? Have the decisions become intuitive or do you experiment with the same material in both genres?

KM: I have experimented with the same material in both genres, and in poetry, too. In fact, there are poems that precede "You Shall Go Out with Joy and Be Led Forth with Peace" from which I've appropriated language and images (the starfruit tree, for example.) There are other poems, too, especially a series I wrote when I was taking a class with David Baker, that are themselves the germs of chapters of the book-length memoir.

The difference, with fiction, is that you have more liberty to transform the raw material, and also to imagine it through characters not yourself (though I suppose you use your own experience of yourself to inform the characterizations.)

Right now, for example, I'm working on a story that unfolds in the form of a sexual history. I wouldn't be afraid to address that material in the nonfiction, but I also fear it wouldn't be terribly interesting, since my own sexual history isn't terribly interesting to anyone except me. But to graft the things you know from your own life experience onto a character who finds himself or herself in an interesting predicament -- well, that's where, in fiction, the magic can happen.

In nonfiction, I don't find it terribly difficult to implicate myself or a character not unlike myself, but to try to get at the darknesses lurking inside characters unlike myself (or both like and not like myself, as these things tend to go), fiction seems like the best route.

Lately I've found that I'm reserving the most explosive events from my past for the nonfiction, and using the fiction to try to imagine my way through experiences I've seen or participated in, but through the eyes of some other involved person -- the mother, the sister, the victim, the perpetrator. But that's not always my working method. I'm not sure I even have a working method, except whatever's working at the moment.

CS: I like the distinction you make in the last paragraph. And it's true, "working methods," if they exist, tend to be a little elusive when it comes to writing.

Since you mentioned "You Shall Go Out with Joy and Be Led Forth with Peace": The essay's title is taken from one of the borrowed Jewish songs young Minor sings at school, which "are faintly reminiscent of sad country songs," and which "really slay [Minor], because there is something earned about that joy; it has come from a place of great pain." By the end of the essay, when Minor speaks at his friend Tony's funeral, he hasn't earned the kind of "joy-from-sadness" espoused by the song, but I couldn't help but think that perhaps the writer Minor, while rendering an artful interpretation of these events, might have earned some of that joy.

KM: I did a reading last spring at Ohio State, and it was terribly hard to get through it, and afterward people were coming up to me and saying the same kind of thing you're saying. It speaks, I think, to one of the fundamental illusions that I (and everyone else, it seems) have been under about the process of writing, that it would be somehow therapeutic.

It's true that I'm proud of that essay. It's helped to put me on the map after years and years of trying. But writing it required me to immerse myself in the interior landscape of the worst part of my childhood for an extended period of time. For months afterward I was having nightmares, and the night after I read it publicly for the first time, I couldn't sleep, and spent the next day walking and walking. The whole book would probably be finished by now, except that I had to put it aside for awhile to get my head straight.

There's something rather selfish about allowing oneself to spiral down into that kind of darkness for the sake of a piece of writing when other people are depending upon you. I know that during the time I was working on "You Shall Go Out with Joy," I was significantly less available to my wife and my son, and not just in terms of time, but also in terms of emotional availability. Somehow, to write as honestly as I wanted to write, I had to become twelve years old again, and strip away perfectly good defense mechanisms so I could revisit pain that I'd buried long ago.

I spent the first five years of my writing life making pretty things out of language. Lee Abbott was always hectoring me about this, but indirectly, by way of pithy sayings I didn't understand: It ought to cost you more than time to get it on the page. That kind of thing. I'm not that smart lots of the time, and for me it took somebody, in this case Michelle Herman, getting in my face and saying, "I don't buy these stories you're writing. What is it you really want to be writing about?" for me to remember what it was that made me want to be a writer in the first place. Even then, I didn't realize what it would cost me to confront my own darkest places until I actually did it. I'm still not sure it's worth it.

If you think about the writers I love who have done this over and over -- Andre Dubus, Graham Greene (who wrote potboilers, sure, but who also wrote very personal books like The Power and the Glory and The End of the Affair), Raymond Carver, Alice Munro -- and you look at their own personal histories and see the way they were often writing so close to the bone, you have to wonder how they were able to sustain it for as long as they did. It had to take a real toll on them personally, and certainly on their families, too. When I think about that, it scares me to death, because I feel like I've crossed some sort of line in the sand -- I don't really want to go back to making pretty things for the sake of making pretty things -- and yet I don't want to live my life only in service of the writing, either, which is the real temptation. It's a tightrope.

CS: It is a tightrope. Some instructors and I were talking to a group of undergraduate seniors in creative writing this past term about "writing in the real world," and one of my colleagues said something very heartfelt about how his commitment to the art trumps pretty much everything, and how he has sacrificed numerous things in his personal life in order to achieve what he's wanted to with his writing. As a twenty-two-year-old, I probably would have rallied behind such a sentiment, but when it came my turn to talk, I offered a different point of view, explaining the reason why I tend to write either very early in the morning or very late at night--because I don't want it to interfere with the rest of my life on a daily basis. I explained that I want to be available to people--not just with my time but with that emotional availability you're talking about. I argued, too, that the external "rewards" of writing--publication, readers--is never going to amount to much in the grand scheme of things. Afterwards, it occurred to me that I hadn't truly had much of the kind of "success" I was somewhat eschewing. You, though, are now officially anthologized, yet you still question whether or not the personal sacrifices are worth it?

KM: I don't really know how to answer the question. From a worldly perspective, the anthology hasn't made me successful at all. I'm still scrapping, still grinding out a massive adjunct teaching load at four schools, still staying up late or getting up early to find time to read and write, still living in an ancient brick apartment, still unable to provide many of the things I'd like to provide for my family. Every once in awhile something comes along -- I have a friend, for example, who works at a mortgage repossession and reselling company. They need someone with a writing background to grind out case studies and other kinds of business documents. It would have paid something like $70,000 a year to start, with built-in escalators every six months. Needless to say, that's a lot more money than I'm making now. The main reason I'm not interested is that I know it would sap all my writing energy and wall me off from the material I care about. There's a sense in which that sounds terribly noble, the decision to not pursue those kinds of opportunities for the sake of art, but there's also a sense in which it is terribly selfish. Because I know that I could buy my wife a house and put money away for retirement and maybe help out family members who need it, and, hell, all kinds of other good things. I have a friend who’s trying to alleviate poverty in Haiti. I could help him. But I won't do it, and all because I want the time and space and mental energy to devote myself to writing that will likely never find a large audience, and whose driving impulse is mainly personal, and therefore, I suppose, selfish. With all that, though, I still feel like it's worth it, so long as I can make time for my family and be good and loving to them and make sure that they have a roof over their heads and food to eat.

CS: Speaking of the time and space and mental energy you devote to writing, what is your writing schedule like? Also, how do you go about deciding on any given day whether you're going to work on a short story, or your memoir, or a poem? Is working in multiple genres a boon or hindrance?

KM: It changes all the time. Right now, for example, I'm supposed to be working on revising the novel and the book-length memoir, but I'm procrastinating by working, off-and-on, on a novella, mostly. But on Sunday I got all excited about a new short story and stayed up all night Sunday, Monday, and Tuesday nights, sleeping about four hours in the early morning. That's a working method I favor but hardly get to do anymore, because of teaching, but it was the lucky week off between the end of Ohio State's summer quarter and the beginning of Capital's fall semester. By Wednesday at 6 pm, I had a 10,500 word first draft that was, quite frankly, a lot more finished than the fourth draft of the novella that's open in the Microsoft Word window right next door. And now I'm tired, and don't have the energy to get back to prose, and probably won't until the weekend, so I'll spend a couple of hours the next few days revising some poems.

I was talking to a friend about this the other day, and he was saying that he didn't have space in his head for more than one story at a time, that the writing of one demanded his complete and sustained attention. I find that my complete and sustained attention to something that isn't working just gives me a headache and causes me to force pages that I later end up cutting anyway. But getting away from a problem for awhile seems to give my unconscious the space it needs to find the solution. The solution usually comes when I'm in the shower, thinking about something else, or while reading a book by a writer who is my polar opposite in language and temperament, or while taking a long walk down Neil Avenue, from 17th to 3rd, and back again.

CS: Once finished drafts of these manuscripts accrue, how do you go about submitting them for publication? Has editing Frostproof Review taught you anything about the process?

KM: That the process is brutal, sure, but also that the cream rises quickly to the top. The best thing I ever had the honor to publish (which is saying an awful lot, when one considers the company it's keeping in the pages of the Frostproof Review) is a novella by Jennifer Spiegel titled "Goodbye, Madagascar." It arrived packaged with a smart cover letter, but who cares? The first sentence made me want to read the second, and the second the third, and in forty-five minutes, I'd read that seventy page story. And then I read it again. And then I called her on the phone in Arizona late at night and said, "I hope nobody else has taken this, because it's the most beautiful thing I've read in a long time."

I don't get fancy with my submissions anymore. I send a three sentence cover letter: Here's my story, here's where I've previously published, thanks for taking the time to read it. Everyone thinks there's a magical formula, but all the editors really care about is whether or not the story or poem or essay knocked them flat, and if it didn't, it probably isn't ready to be published, anyway. They're doing you a favor by rejecting you. At least, that's how I think about it.

CS: Besides showcasing non-fiction in lieu of fiction, something else that interested me about the Twentysomething anthology was the fact that they solicited manuscripts for inclusion in the anthology from the general public, rather than from writing programs and/or literary magazines. How did you find out about the anthology, and how did you choose what to submit to them? What kind of effect do you think their "open" submission policy had on the anthology?

KM: I think it made possible the discovery of a lot of new writers. The very nature of the selection process of ordinary anthologies tends to privelege work from established writers and work that was originally published in the more prestigious journals. The sheer workload involved in screening makes that a practical reality. If a story begins slowly, but it's written by Alice Munro or William Trevor, or it was originally published in the Georgia Review or Ploughshares, the odds are still pretty good that the story will reward the time required to read it. But, as I know from editing even a small literary journal, one might not extend the same generosity to an unpublished writer from nowhere familiar. It's not a big conspiracy; it's just a matter of time. There are only so many hours in the day, and if something doesn't seem immediately promising, it's not going to get the same kind of attention as something that holds promise for one reason or another.

The Twentysomething Essays anthology took most of that out of the equation, because everyone was unknown, and all the essays were unpublished at the time of submission. And the results speak for themselves. There are essays in that volume, like Jennifer Glaser's "Sex and the Sickbed," or Mary Beth Ellis's "The Waltz," or Joey Franklin's "Working at Wendy's," that I, at least, can't stop thinking about. Random House was smart enough to cast a wide net and find them, and now, if they're much like me, they'll be inclined to want to dance with the one who brung 'em when it's time to talk book deal.

CS: On the subject of book deals: You mentioned that you're in the process of revising a novel and the memoir. Where are you at in the revision process? When do you think we'll see "You Shall Go Out with Joy and Be Led Forth with Peace" in between the covers of a book filled with only Kyle Minor's writing?

KM: For both the novel and the memoir, I have all these pages I keep taking out and putting back in, and it's not anything like the proverbial taking-out and putting-in of commas that means the thing is done. It's more like I've not yet really got a handle on the shape of either thing, and I'm not ready, yet, to even send them to my trusted first readers.

The memoir, I suspect, will be done first. My friend Don Pollock has already taken me to task for not having it done already, and with good reason: I have this nice first-look arrangement with Random House, and the thought that I'd wait too long and blow my chances at placing it with one of the best publishing houses in the world (not to mention the chance to work again with Matt Kellogg, who is as fine an editor as I've ever met), quite frankly scares me almost as much as the prospect of finishing it and sending it out into the world.

But the truth is I've been spending most of the summer writing a novella and some short stories. I don't want to send either one out into the world until they're ready, because I've already had the experience of being haunted by early publication of work that didn't yet know what it wanted to be. I think with a first book, when one considers how few chances you actually have to publish a book in an entire lifetime, that caution ought to be the order of the day. With the novel, especially, I plan to take my good sweet time.

In my secret, greedy heart, though, I daydream about winning one of the big short story collection contests, like the Flannery O'Connor or the Drue Heinz, and seeing simultaneous publication of the fiction and the nonfiction books. Three years at Ohio State, though, in a community of writers so extraordinary, has made me really reevaluate what kind of book I would want to send out. There are four first-class writers of short fiction (Lee Abbott, Michelle Herman, Lee Martin, and Erin McGraw) on the faculty, and you can't help picking up one of their books now and again, and reading some stories, and realizing exactly how excellent and well-crafted and moving a story has to be before it's worth collecting. And then your classmates in workshop are Donald Ray Pollock or Holly Goddard Jones, and both of them writing and publishing stories as good as anything in your Norton anthology; and then there's recent graduate Christopher Coake's collection We're in Trouble, which is maybe the best short story collection published in America in the last five years. Those writers have become a sort of benchmark for me, because I guess I'm a person who needs benchmarks. I don't want to publish a book of stories until I know I've written one that could sit proudly on the shelf alongside theirs, and that's no small feat. Maybe when I'm fifty.

CS: I’m with you on caution being the order of the day, but fifty? That might push you toward an entirely different anthology.

KM: Sometimes I wonder if it might not be more useful for readers if publishers and book reviewers reserved all the energy and attention they like to lavish upon hot young writers, and bestowed it, instead, on writers over fifty, sixty, seventy, who have so much more lived life to write about. It used to be that the great writers (Hemingway, Faulkner, Fitzgerald, that generation) wrote their great books as young men (and wasn’t it always men, back then, who were considered the great writers?) But now, and maybe because writers are eating better and working out more and drinking less, it seems that our better writers are doing their best work in their waning years. I’m thinking about Roth’s American trilogy, and Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead, and the Peter Taylor of The Old Forest, and the William Maxwell of So Long, See You Tomorrow. And then there’s Annie Proulx, who didn’t even start publishing fiction until she was well into her fifties. Or, closer to home, Lee K. Abbott’s recent experiments with a more public kind of story, such as “One of Star Wars, One of Doom,” which, now that five years have passed and we are getting access to documents left behind by the killers for the first time, is turning out to be more right about the perpetrators of the Columbine incident than the journalism that was being written at the same time. They weren’t monsters; they were real flesh and blood human beings with petty grievances not terribly unlike our own: They wanted girls to like them. And that whole affair is strangely reminiscent of the circumstances surrounding the publication of Eudora Welty’s final (and possibly finest) story “Where is the Voice Coming From?” which so accurately (and eerily) predicted the person, circumstances, and mindset of Medgar Evers’s killer that, when the man was finally arrested, she was forced to change some of the details in her story in the interest of not unduly influencing the prosecution.

So, yes, I’d welcome the chance to be in such an anthology in twenty or thirty years or so. Fiftysomething Stories by Fiftysomething Writers? Sixty by Sixty? Can you imagine how thrilling it would be to keep company like that?

3 comments:

That made me want to buy the book. I will get my copy today.

This was such an insightful, honest, and inspiring interview. I'm looking forward to reading my copy.

I appreciate his perspective on memoir versus fictional narratives.

Post a Comment